![]() Dr Eve Olney contemplates what justice for victims of domestic violence might look like if we shift responsibility away from the legal institutions and into the social realm – a community response to patriarchal violence.

Dr Eve Olney contemplates what justice for victims of domestic violence might look like if we shift responsibility away from the legal institutions and into the social realm – a community response to patriarchal violence.

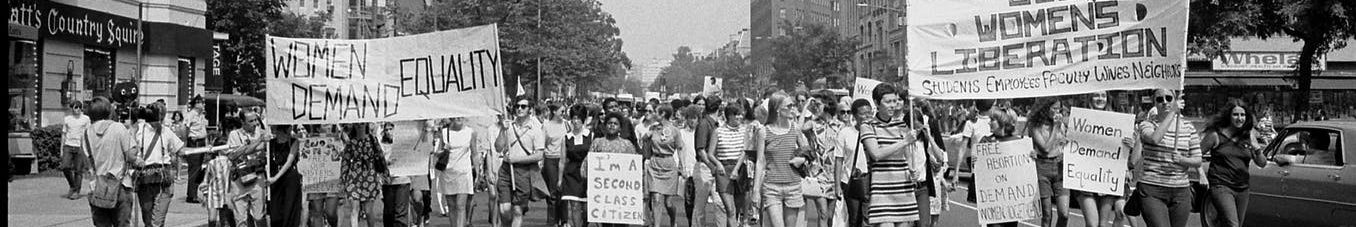

DOMESTIC VIOLENCE IS A COMMUNITY ISSUE: HOW SHOULD THE COMMUNITY RESPOND?

by Dr Eve Olney

In a recent Irish Times online article, I have far too many stories: 30 Irish women on harassment and assault, by Damian Cullen, Mar 16, 2021, two particular statements stayed with me, from the outlined accounts of violence and aggression against women. These were, firstly, that ‘…so much of [women’s] lives [are] spent on high alert’, and secondly how girls and women learn how ‘to modify [their] behaviour in an attempt to mitigate risk. We learn to consider our personal safety as second nature. It influences our decisions all the time and it results in us perceiving situations differently from men.’ Rather depressingly, this is the daily reality of most women. The fact that my fifteen year old daughter is now also being enveloped by this oppressive phenomenon, in disturbing and upsetting ways for a mother to behold, is a further demoralizing indication to me that, despite so much activism and current media awareness on this topic, nothing is changing.

Tangentially to this, I have recently engaged in arguments with people regarding my insistence of using the term patriarchy when distinguishing oppressive systems of social behaviour and attitudes. The argument presented to me is that this term should no longer be used as it offensive to some of those (men) who are unnecessarily tainted by this categorising of abuses of power. Passing my daughter’s bedroom I overhear her having a similar argument with someone on line. I hear her say, “Yes, it’s not all men, but its 93% of women who are badly affected…Not all white people are racist but enough of them are that we still need to use the term racism.” I think again of what living our lives ‘on high alert’ means and how it impacts on women’s everyday behaviours and sense of themselves both within social spaces and, also, what of that they carry home with them? The idea of ‘home’ then leads me to that category of oppression called ‘domestic violence’, where the space you are told you belong to – a home – is the most dangerous, threatening, isolating and oppressive place you can be. The notion of an unlivable environment comes into the frame, where someone is embodying the constant threat of violence.

Currently in Ireland our laws against oppression and violence are meant to alter patriarchal oppressive behaviour towards women. This is obviously not working in practice. Behaviours are not being altered and in fact, it seems, are on the increase since the beginning of the Covid-19 pandemic lockdown. In addition, listening to some accounts of support workers assisting people who suffer from domestic violence, law seems more of an interpretive practice and is never a guarantee that dealing with the issue through the courts will bring the necessary outcomes, i.e., enabling the woman (and perhaps children) to live a life that she is in direct control of.

So if we were to collectively admit that the courts, the laws, are not fit for purpose what then?

What if we were to shift our thinking from a reliance on the legal institutions that are meant to be serving us, to a focus on the responsibility of the social realm within which these acts of violence and intimidation are enacted? What might that look like? How might that be effective? How might it even be imagined? It is easier to envisage if we consider an existing example. Miran Kakaee, offers us some insight as to what that might look within his reflection on how the people of the Autonomous Administration of North and East Syria (NES) apply a ‘democratic confederalist approach to addressing patriarchal violence’. His article sets out to, ‘assess the traditional notion of law and punishment as a solution for dealing with patriarchal violence’, by looking at NES, ‘as a fairly successful example of…a justice system that is based on principles of restorative and transformative justice’.

The social political structures of democratic confederalism were conceived by social ecologist Murray Bookchin as an alternative to the so-called representative democratic structures that govern most of the Western world. Kurdish leader Abdullah Ocalan established such a system in which the main ‘decision-making processes lie with the communities’, and, ‘the basic power of decision rests with the local grass-roots institutions’.

Therefore there is no one authoritative State power that punishes those who cause harm to others. Instead, there are a number of different ‘Justice Platforms’ of committees and other social practices that are established as an acknowledgement that, ‘in order to eliminate patriarchy a societal transformation is needed, and in order to transform society, the individuals constituting society must be transformed as well’.

There is not room to go into the details of such a complex system here but some general practices include, organized women’s educational committees that enable women in becoming ‘self-reliant’; women’s organizations that ‘intervene in cases of patriarchal violence’; committees that are solely made up of women investigating cases; social sanctions against the aggressor, including boycotting businesses if relevant; ‘”exclusion from some public rights”’ and educational training of the perpetrator until such time that they have convincingly ‘changed’. Kakaee acknowledges in his article the success of this approach being reflected in the drastic reduction in cases of violence against women, whilst also acknowledging the difficulty of any of these practices being adopted by Western Europeans, as he argues, we would need to conceive an entirely different system of law.

There is an endemic understanding within the NES example that having laws alone will never be enough in tackling domestic violence, and, as Kakaee argues, ‘law is only necessary in a society which is not living as a community, or differently put: where law begins, community ends’.

His report definitely deserves consideration in terms of how far off we currently are from addressing patriarchal violence within our own so-called democratic State.